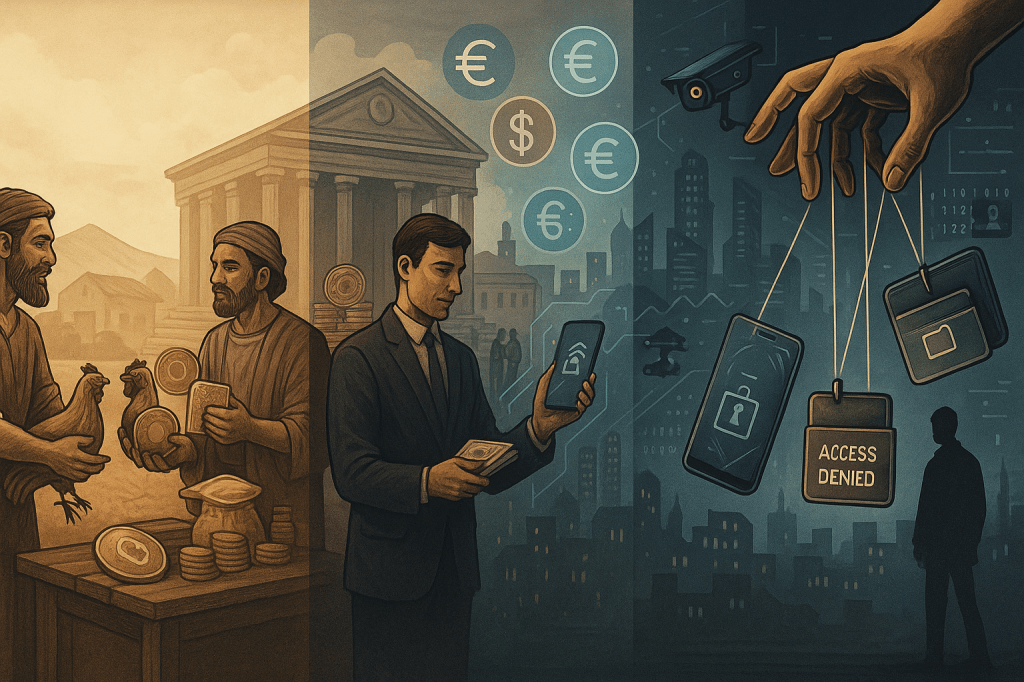

Money has always played a central role in shaping human societies, and its evolution tells a story of increasing control, surveillance, and centralization. From the early barter system—where people traded goods directly, relying on mutual needs—to today’s digital currencies, the journey of money reflects not just innovation but also the shifting balance of power. While the barter system was limited and inefficient, it was inherently private and anonymous. No central authority dictated the terms of exchange. With the introduction of metal coins paper money, they became more standardized and portable, but it also marked the beginning of centralized control over value.

Fast forward to the 21st century, digital money dominates global financial systems. With every transaction occurring electronically, through online banking or contactless cards, the convenience is undeniable. However, this digital shift comes at a steep cost. Each transaction leaves a digital footprint, feeding into a vast ecosystem of data surveillance.

The rise of Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) and smart money represents not just technological progress but a potential gateway to unprecedented financial control. These state-issued digital currencies are programmable and traceable, allowing central authorities to monitor, influence, or even restrict how money is spent.

This level of oversight is deeply concerning. In the name of efficiency and security, individuals’ financial behaviors can be analyzed, categorized, and judged. Governments might justify these actions with promises of combating fraud or increasing financial inclusion, but the trade-offs are stark. Privacy erodes when every transaction can be tracked. Autonomy diminishes when money can be programmed to expire, be spent only in certain ways, or even be withheld based on compliance with government policies.

Smart money, powered by blockchain and AI, introduces the possibility of conditional spending. While it may ensure that welfare payments are used appropriately, it also means that personal spending choices can be externally dictated. This could set a precedent for paternalistic financial governance where governments decide what is “responsible” or “acceptable” consumption.

AI’s role in monitoring transactions adds another layer of concern. In countries like China, the integration of financial behavior with digital identity and social credit systems illustrates how easily financial technology can morph into a mechanism of social control.

A low credit score, influenced by one’s purchases, online activities, or associations, can result in restricted travel, limited access to services, or public shaming. Such systems demonstrate the terrifying potential of AI-enhanced financial surveillance.

The scenarios for the future are not all bright. An optimistic view suggests greater access, lower costs, and reduced crime. But a more realistic, if not pessimistic, vision foresees centralized control, digital disenfranchisement, and loss of personal freedoms.

The ability of a government to freeze assets, deny transactions, or conditionally approve spending creates a fragile reality where dissent or non-compliance can be financially punished.

In Romania, the adoption of digital financial systems is advancing. Yet, without robust public debate and legal safeguards, the country could follow paths like more authoritarian models. Trust in government and institutions is already a sensitive issue; giving them unchecked access to financial data could deepen public skepticism and resistance.

As digital money continues to replace physical cash, we must ask ourselves whether the convenience it offers is worth the potential cost to our freedom. Will digital currencies liberate us through innovation, or will they become tools of subtle oppression?

ALESSIA SZMOLEN